Clay soil isn’t all bad when it comes to gardening, but heavy clay or soil that is highly compacted can be a nightmare to work with. Plants need to be able to put their roots down and get both water and good aeration from the soil, so most will be unhappy in compacted clay.

One conventional way to deal with compaction or clay is to constantly till the soil. This does improve aeration and drainage in the short term, but it has a very negative effect on soil structure in the long term and destroys soil life. Sometimes you do have to have to till or use a disk harrow to break up your clay for the first time, but moving towards a no-till or low-till system is ultimately best for soil, plant, and human health.

Using specific plants to break up clay soil is a completely natural way to deal with compaction and will keep improving the condition and structure of your soil in the long run. This is frequently called “biological tillage” and is much healthier for your soil. The best plants for the job are typically hardy plants with deep taproots or a dense fibrous root system. These plants literally break through the clay, leaving airways and drainage passages behind them.

Here’s a look at the top plants for clay soil that will fight compaction and make gardening easier (and more enjoyable!) for you.

This post includes affiliate links. If you make a purchase using one of these links, Together Time Family will receive a commission at no additional cost to you.

As you work to improve your soil with plants that grow in clay, you can gain greater benefits by remembering three things:

- First and foremost, be thankful for your clay soil! It feels hard to work with, but it is frequently nutrient rich and holds water well. Once you alleviate compaction, build your soil food web, and add organic matter, you will have an amazing garden.

- Polyculture cover crops and green manures frequently out-perform monocultures. For a fascinating look at this, check out Gabe Brown’s book From Dirt to Soil.

- Inoculating your seeds with beneficial microbes improves your soil health even more.

Unfortunately, not all of the plants that are good for breaking up clay soil can partner with microbes. Brassicas, buckwheat, and dock are non-mycorrhizal. My favorite general use inoculant, for plants that can use it, is Myco Bliss. It’s a great value and I’ve had a lot of success with it. You can use it to inoculate seeds or water it in after planting. If you get some, make sure to use it with your tomatoes. I could not believe how quickly my tomatoes grew when I started them in soil inoculated with Myco Bliss.

Best Plants for Breaking up Clay Soil & Compaction

We’re working on improving extremely dense clay in our West Virginia location. I’m enrolled in Matt Powers’s Regenerative Soil course and this is the basic, quick version of advice he gave me:

- Broadfork the soil

- Add compost

- Broadfork again the next day

- Plant inoculated seeds

- Use a light scatter mulch to protect the seeds as they sprout

Please, please be careful if you decide to use straw or hay on your garden. Ask questions and do not use hay that’s been sprayed with chemicals. Herbicides in hay, and animal manure from animals that ate sprayed hay, can ruin your garden for years to come.

The work and wait are worth it. Clay has the possibility to form amazing soil that holds water and produces nutrient dense food for your family. If you have challenging clay, here are some of the best plants you can grow:

Daikon Radish (Raphanus sativus var. longipinnatus)

Daikon radishes are no ordinary radishes. They grow long white tap roots that can reach up to two feet long! These deep roots are highly effective at breaking up clay or compacted soil and will add organic matter to the soil if left in the ground.

If you choose to, you can harvest a few daikon radishes to eat. They have a milder flavor than standard radishes but still have a peppery kick and a slight sweetness. Daikons are very crisp and crunchy when fresh and almost potato-like when cooked. I have steamed daikon and mashed it like potatoes. It did have a light radish-y flavor, so it wasn’t exactly the same, but it was tasty with butter and cheese.

However, for the maximum benefit to your soil, leave most of the radishes in the ground. They will eventually rot and return nutrients to the soil as well as improve drainage, aeration, etc. Simply cut the tops off at the end of the season and compost, if you want, while leaving the roots in place. They will winter kill in most zones, do you don’t need to cut off the tops unless you want to.

The daikon below are growing in a garden bed next to some lettuce, but it gives you an idea of what they look like.

Artichoke (Cynara cardunculus var. scolymus)

You may never have thought of growing artichokes before, but their long taproots help to break up clay soil, plus they’re both edible and beauitful. In most zones, artichokes should be treated as an annual plant, although they may overwinter in zone 8 or higher.

Unless you live in a mild climate, look for a quick-growing cultivar that will produce in one season. You can harvest the buds (the edible part) in late summer or early fall. Once the harvest is over, chop the plants down and let them decompose on top of the soil. The artichoke you eat is the immature flower bud. If you let it blossom, it is gorgeous:

Artichokes belong to the thistle family, so be sure to wear gloves as you work! Don’t have comfortable gardening gloves? Be sure to check out our guide to the best cut resistant gloves, including sizes for women and children.

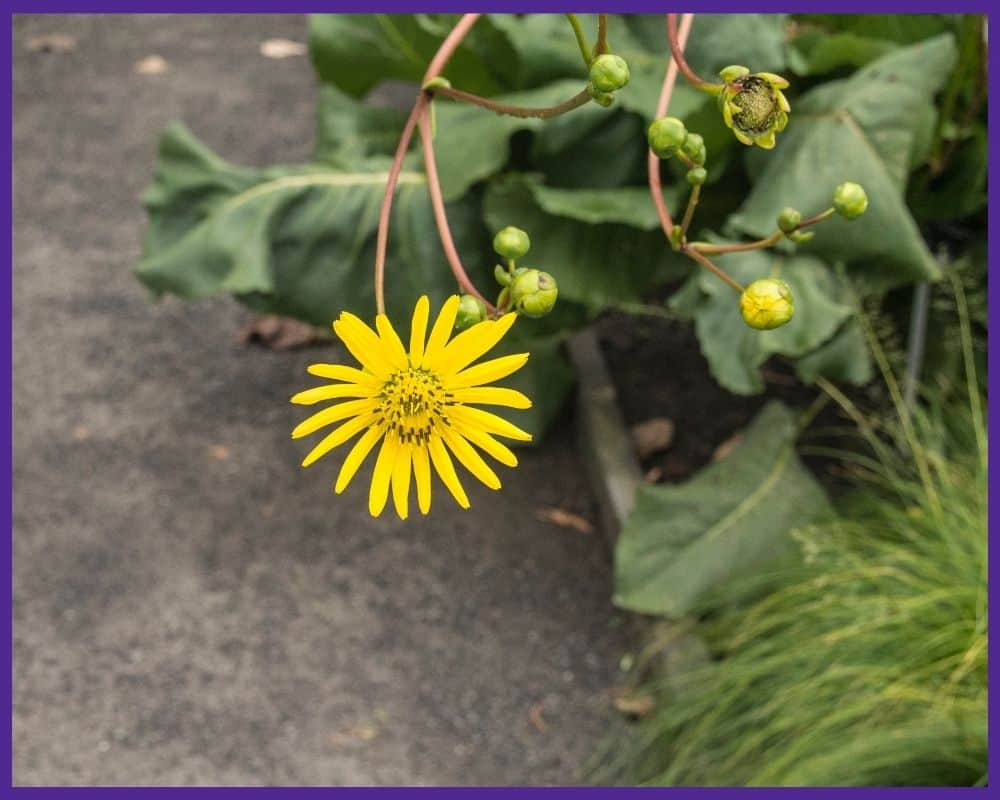

Prairie Dock (Silphium terebinthinaceum)

Prairie dock is a very rugged plant that can grow a taproot nearly as deep as the flowers are tall (which means up to ten feet!). This is what makes it one of the best plants for clay soil, although you’ll need to have enough space to grow this large flower.

Keep in mind that prairie dock is a perennial, so it won’t necessarily grow super tall in a single season. It works best for large areas of clay or compacted soil that may need several years of work— or for heavy clay where you can’t get anything else to grow.

Along with breaking up the soil, prairie dock will reward you with large golden-yellow flowers and textured foliage. Dock cannot partner with mycorrhizal fungi so there is no need to inoculate.

Cowpeas (Vigna unguiculata)

Cowpeas (also known as black-eyed peas) are legumes that can be used as a cover crop for clay soil. They don’t have deep taproots like the previously mentioned plants, but they do develop a very dense root system that effectively helps to break up compacted soil.

Another great thing about planting legumes is that they fix nitrogen in the soil. This will help your soil to be more fertile after the cowpeas are gone. For maximum benefit, make sure to use a legume inoculant.

Although you can buy “official” seed packages, many people have success with planting bags of peas from the store. Black eyed peas are typically easy to find. This year I’m planting a big bag of black-eyed peas I got from Azure Standard. For best results and fast germination, pre-soak your seeds the night before you plan to plant.

For maximum nitrogen, cut the cowpeas down just before or after flowering. If you aren’t as concerned about nitrogen, allow them to flower (which will attract beneficial insects) and harvest the beans when they are ready. The plants will be killed by a frost, and you can simply let them decompose over the winter.

Milkweed (Asclepias spp.)

Milkweed is a very important native flower. As you may know, it and butterfly weed are the only existing food sources for the Monarch butterfly caterpillars, which makes them hugely important in conservation efforts for Monarchs. If you can’t find milkweed seeds locally, I love Etsy seller Southern Seed Exchange. They always ship promptly and have high quality seed.

To go along with this, most milkweed varieties also develop deep taproot systems (or dense fibrous roots) that help to break up clay and compacted soil. They typically thrive in dry, lightweight soil but adapt surprisingly well to clay conditions.

If your clay soil tends to be on the wet side, swamp milkweed (A. incarnata) is probably the best choice. It, like other milkweeds, is a perennial, so use it for areas where it can be grown long-term, gradually improving the soil.

Sunflowers (Helianthus annuus)

Sunflowers may be the most ornamental plants for clay soil and breaking up compaction. These cheerful members of the daisy family grow anywhere from a few feet to upwards of eight feet in a single season! Sunflowers do partner with fungi, so grab some inoculate to help your plants grow better. Data show that plants inoculated with mycorrhizal fungi grow better and produce more while using less water thanks to their increased root volume and enhanced nutrient uptake.

Unlike many other ornamentals, sunflowers are fairly tolerant of compacted soil and establish vigorous roots. They may not grow as tall as they would otherwise when planted in heavy clay, but they will leave the soil better off when they’re gone.

When the season is over, leave the sunflower heads on for a while so that birds can feed on them (and harvest some for yourself). If you want to know more about collecting sunflower seeds, stop by this guide to harvesting sunflower seeds. In late winter or early spring, cut off the stalk at ground level, but leave the roots in the ground to decompose. The stalks can be composted or left in place to armor the soil.

Armoring the soil is a Gabe Brown concept (and he has actually used sunflowers for this purpose). To learn more, read From Dirt to Soil. It’s a very easy read that will leave you feeling hopeful about the possibilities of regenerative agriculture. You will learn that it’s possible to both heal the planet and feed the world.

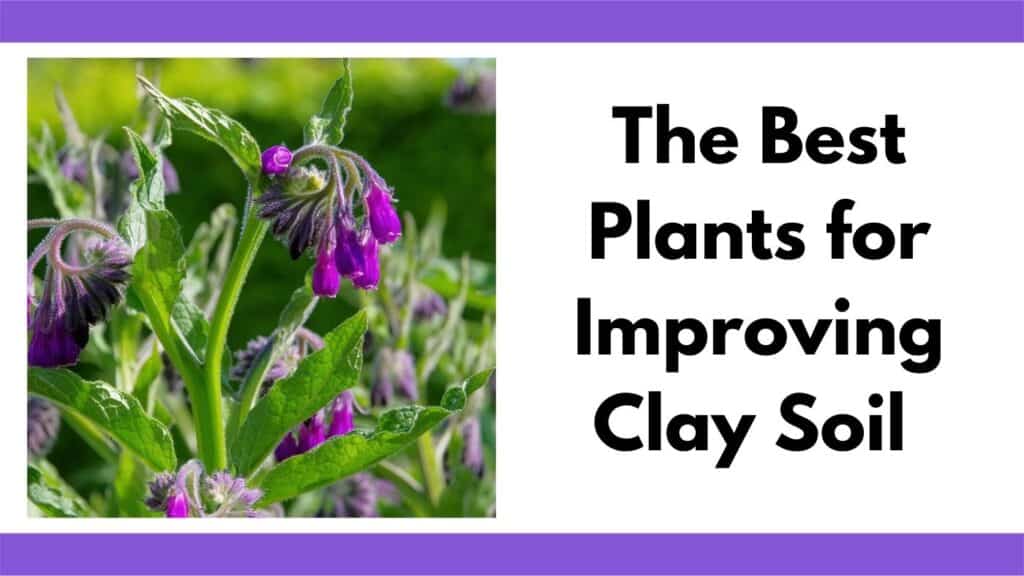

Comfrey (Symphytum officinale)

Comfrey is a perennial herb that is often used in permaculture for its many soil benefits. Its vigorous root system breaks through compaction and creates channels for water to flow through as well as better aeration.

Another benefit of comfrey is that the leaves can be cut off and used as green mulch or added to your compost. You can simply layer them on top of your soil where they will break down and improve your soil even more over time. Comfrey is said to be a fantastic accumulator of nutrients, so practicing chop and drop with the leaves adds nutrients to the soil while building organic matter. Comfrey is also popular for feeding to chickens and rabbits.

There is a surprising amount of controversy surrounding comfrey. Some people are afraid it will release toxins in the form of pyrrolizidine alkaloids that make even nearby plants unsafe to eat. Other people have fed their animals almost exclusively on comfrey.

Comfrey has demonstrated healing powers for would healing when used externally, but most people recommend avoiding internal use in humans. Like with all things, I think moderation is best. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids do exist in comfrey and they can be toxic. Older leaves have less PAs and drying also mitigates the PA content. Learn more about comfrey from Permaculture News so you can make an informed decision about whether or not you want to use comfrey leaves for yourself or animals, or just want to use it to improve your soil.

Though technically a perennial, comfrey can also be grown as an annual to prepare an area for planting. This can be a tricky proposition, though, since it spread through its roots. I prefer to keep comfrey in an area of its own. Make sure to give each plant at least 3 feet of space so its root system can expand.

Be careful when planting comfrey. Comfrey can spread vigorously. To help mitigate spreading, get Bocking 14 cuttings because they are sterile and only spread through roots, not seeds. (Other varieties can spread through both means.) The picture shown below is a very young, small comfrey plant that grew from a cutting I purchased from this Etsy seller. It will grow much larger. (The pictured plant had only been in the ground for a few weeks.)

Buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum)

Buckwheat is one of the top plants for clay soil because it’s quick-growing and develops numerous fine roots that help to break up the topsoil. It works best as a summer cover crop that gets planted in spring or early summer. It’s a quick way to add organic matter to the soil and you can get multiple rounds in during a single growing season in many climates.

Not only does buckwheat help to break up the soil, it is also very efficient at taking up phosphorus. If you return the plant to the soil after chopping it down, all of the stored phosphorus will mix in and help build soil fertility. Please do return the plants to the soil – they break down quickly and add organic matter to further improve your clay.

If your soil is incredibly compacted, you will need to break it up a little before planting buckwheat. I’ve planted buckwheat on clay I broadforked, clay I didn’t broadfork, and even on compacted sand that used to be under a pool. Even though the lumps of clay were still large, the buckwheat planted on broadforked clay did very well. The buckwheat planted on the completely compacted soil was incredibly stunted. Broadforking clay is hard work, but it pays off:

One thing to note with buckwheat is that it needs to be chopped down before plants set seed (about a week after flowering). When the plant is at full bloom, it has the most nutrient contents so it’s the best time to cut the plants back, anyway. The stems are watery and won’t tie up nitrogen in the soil, so you can cut the buckwheat back and plant into the area immediately while using the buckwheat stems for a mulch. I throw sow more buckwheat, chop down the old plants, and allow the stems to protect the new seeds from predation until they sprout a week or two later.

I use my scythe (yes, a scythe) to cut back my buckwheat at full bloom, but you can also use a weed eater, especially if it has a blade attachment, or just cut it off by hand. You can also rip it out of the ground by hand, but I prefer to leave the roots in the soil. Tired of garden gloves that are too big and clunky? Check out my favorite gloves that actually fit smaller hands in this guide to cut-resistant garden gloves.

Buckwheat is non-mycorrhizal and does not benefit from inoculation.

The photo below is not buckwheat, but I wanted to show you that I really do have a scythe.

Mustard (Brassica spp.)

Brassicas tend to grow better in clay soil than many other plants, and mustard is a great example of this.

If you aren’t familiar with them, mustard plants are cabbage relatives that bloom with bright yellow flowers. The leaves of the plants can be harvested as greens, and the seeds of certain varieties can be pressed to make mustard oil. Mustard is a traditional cover crop in California’s wine country.

Mustard is great for clay soil because it has a tough, fibrous root system that busts through compaction. It also produces a lot of biomass that can be chopped up and added to your soil at the end of the season.

However, it’s very important to cut mustard back before it goes to seed. This plant becomes weed-like in certain areas if allowed to spread itself by seed.

All brassicas are non-mycorrhizal, though they can benefit from a specific partnership involving trichoderma.

Root Crops

One trick that home gardeners can easily benefit from is to use ordinary root crops like carrots, radishes, and rutabagas to start breaking up clay soil. These specific vegetables naturally create channels in the top 4-8” of the soil for water and air to travel through. (That is a conservative estimate – in soil that is more loose, these plants will extend their roots multiple feet into the ground.)

If you want to use this method, don’t plan on eating your vegetables. They will most likely be scraggly anyways as they try to grow through clay or compacted soil, and leaving them in the ground keeps the newly created channels in place and adds biomass to the soil.

At the end of the growing season, simply chop off the tops of your root veggies and allow the roots to naturally decompose (a few may resprout next spring). You can skip cutting the tops off if you don’t mind the possibility of having your plants go to seed.

Winning the Battle with Clay Soil

Along with adding lots of organic matter to your soil, utilizing the plants on this list is one of the best ways to break up compaction and naturally improve clay soil. If your soil is extremely heavy or compacted, it may take a few seasons of work for you to notice a difference, but you’ll get there eventually!

To improve your soil the quickest way, make use of these top plants for clay soil by both allowing them to grow deep roots that break up compaction and adding the leaves back to the soil at the end of the growing season.

This will improve drainage, soil structure, and fertility and will make way for new plants to be planted next year.

Popular summer vegetables and herbs

Discover how to grow popular vegetables and herbs in your backyard garden or container garden with these in-depth vegetable growing guides.

7 Easiest Vegetables to Grow for an Abundant Harvest (and 5 to avoid!)

Discover the easiest vegetables to grow for beginners so you can have a healthy, successful garden.

Discover these must-know tips for planting yellow squash and common squash growing mistakes and problems.

How to Pick and Preserve Cherry Tomatoes (plus drool-worthy cherry tomato varieties to try)

Discover how to pick and preserve delicious cherry tomatoes.

Must-Know Zucchini Companion Plants (and 5 plants to avoid)

Zucchini are a summer garden must-have. Learn how to companion plant them for a healthier, more productive garden.

How to Harvest Basil (Must-know tip for an abundant harvest!)

One basil plant can provide you enough for fresh eating and drying for homegrown basil all winter long when you discover how to harvest basil the correct way.

How to Harvest Parsley (without killing the plant)

One parsley plant can provide you with an ample harvest all season long...if you know how to pick it the correct way. Discover how to harvest parsley with this comprehensive guide and video!

Harvesting Tomatoes - How and When to Pick your Tomatoes

Discover how to harvest tomatoes and how to tell when they're ready to pick - even heirloom varieties with different colors.

Natasha Garcia-Lopez is an avoid home-gardener and proud owner of 88 acres of land in rural West Virginia. She was a member of the Association for Living History Farms and Agricultural Museums for many years and is currently enrolled in the Oregon State University Master Gardner Short Course program so she can better assist you with your gardening questions.She holds a certificate in natural skincare from the School of Natural Skincare.

Leave a Reply